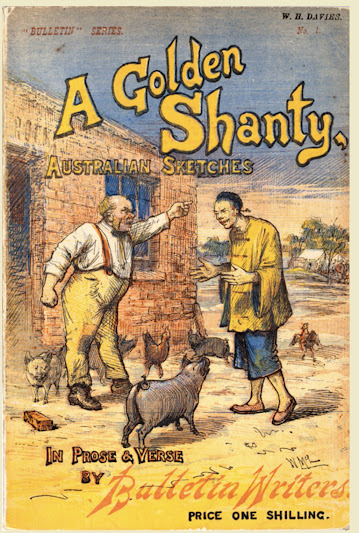

'A Profitable Pub' by Edward Dyson: the first published Australian Short Story.

About ten years ago, not a day’s tramp from Ballarat, set well back from a dusty track that started nowhere in particular and had no destination worth mentioning, stood the Shamrock Hotel. It was a low, rambling, disjointed structure, and bore strong evidence of having been designed by an amateur artist in a moment of vinous frenzy. It reached out in several well-defined angles, and had a lean-to building stuck on here and there; numerous outhouses were dropped down about it promiscuously; its walls were propped up in places with logs, and its moss-covered shingle roof, bowed down with the weight of years and a great accumulation of stones, hoop-iron, jam-tins, broken glassware, and dried ’possum skins, bulged threateningly, on the verge of utter collapse. The Shamrock was built of sun-dried bricks, of an unhealthy, bilious tint. Its dirty, shattered windows were plugged in places with old hats and discarded female apparel, and draped with green blinds, many of which had broken their moorings, and hung despondently by one corner. Groups of ungainly fowls coursed the succulent grasshopper before the bar door; a moody, distempered goat rubbed her ribs against a shattered trough roughly hewn from the butt of a tree, and a matronly old sow of spare proportions wallowed complacently in the dust of the road, surrounded by her squealing brood.

A battered sign hung out over the door of the Shamrock, informing people that Michael Doyle was licensed to sell fermented and spirituous liquors, and that good accommodation could be afforded to both man and beast at the lowest current rates. But that sign was most unreliable; the man who applied to be accommodated with anything beyond ardent beverages—liquors so fiery that they “bit all the way down”—evoked the astonishment of the proprietor. Bed and board were quite out of the province of the Shamrock. There was, in fact, only one couch professedly at the disposal of the weary wayfarer, and this, according to the statement of the few persons who had ever ventured to try it, seemed stuffed with old boots and stubble; it was located immediately beneath a hen-roost, which was the resting-place of a maternal fowl, addicted on occasion to nursing her chickens upon the tired sleeper’s chest. The “turnover” at the Shamrock was not at all extensive, for, saving an occasional agricultural labourer who came from “beyant”— which was the versatile host’s way of designating any part within a radius of five miles—to revel in an occasional “spree,” the trade was confined to the passing “cockatoo” farmer, who invariably arrived on a bony, drooping prad, took a drink, and shuffled away amid clouds of dust.

|

| Edward Dyson |

The only other dwellings within sight of the Shamrock were a cluster of frail, ramshackle huts, compiled of slabs, scraps of matting, zinc, and gunny-bag. These were the habitations of a colony of squalid, gibbering Chinese fossickers, who herded together like hogs in a crowded pen, as if they had been restricted to that spot on pain of death, or its equivalent, a washing.

About a quarter of a mile behind the Shamrock ran, or rather crawled, the sluggish waters of the Yellow Creek. Once upon a time, when the Shamrock was first built, the creek was a beautiful limpid rivulet, running between verdant banks; but an enterprising prospector wandering that way, and liking the indications, put down a shaft, and bottomed on “the wash” at twenty feet, getting half an ounce to the dish. A rush set in, and within twelve months the banks of the creek, for a distance of two miles, were denuded of their timber, torn up, and covered with unsightly heaps. The creek had been diverted from its natural course half a dozen times, and hundreds of diggers, like busy ants, delved into the earth and covered its surface with red, white, and yellow tips. Then the miners left almost as suddenly as they had come; the Shamrock, which had resounded with wild revelry, became as silent as a morgue, and desolation brooded on the face of the country. When Mr. Michael Doyle, whose greatest ambition in life had been to become lord of a “pub.,” invested in that lucrative country property, saplings were growing between the deserted holes of the diggings, and agriculture had superseded the mining industry in those parts.

Landlord Doyle was of Irish extraction; his stock was so old that everybody had forgotten where and when it originated, but Mickey was not proud—he assumed no unnecessary style, and his personal appearance would not have led you to infer that there had been a king in his family, and that his paternal progenitor had killed a landlord “wanst.” Mickey was a small, scraggy man, with a mop of grizzled hair and a little red, humorous face, ever bristling with auburn stubble. His trousers were the most striking things about him; they were built on the premises, and always contained enough stuff to make him a full suit and a winter overcoat. Mrs. Doyle manufactured those pants after plans and specifications of her own designing, and was mighty proud when Michael would yank them up into his armpits, and amble round, peering about discontentedly over the waistband. “They wus th’ great savin in weskits,” she said.

Of late years it had taken all Mr. Doyle’s ingenuity to make ends meet. The tribe of dirty, unkempt urchins who swarmed about the place “took a power of feedin’,” and Mrs. D. herself was “th’ big ater.” “Ye do be atin’ twinty-four hours a day,” her lord was wont to remark, “and thin yez must get up av noights for more. Whin ye’r not atin’ ye’r munchin’ a schnack, bad cess t’ye.”

In order to provide the provender for his unreasonably hungry family, Mickey had been compelled to supplement his takings as a Boniface by acting alternately as fossicker, charcoal-burner, and “wood-jamber;” but it came “terrible hard” on the little man, who waxed thinner and thinner, and sank deeper into his trousers every year. Then, to augment his troubles, came that pestiferous heathen, the teetotal Chinee. One hot summer’s day he arrived in numbers, like a plague, armed with picks, shovels, dishes, cradles, and tubs, and with a clatter of tools and a babble of grotesque gibberish, camped by the creek and refused to go away again. The awesome solitude of the abandoned diggings was ruthlessly broken. The deserted field, with its white mounds and decaying windlass-stands fallen aslant, which had lain like a long-forgotten cemetery buried in primeval forest, was now desecrated by the hand of the Mongol, and the sound of his weird, Oriental oaths. The Chows swarmed over the spot, tearing open old sores, shovelling old tips, sluicing old tailings, digging, cradling, puddling, ferreting, into every nook and cranny.

Mr. Doyle observed the foreign invasion with mingled feelings of righteous anger and pained solicitude. He had found fossicking by the creek very handy to fall back upon when the wood-jambing trade was not brisk; but now that industry was ruined by Chinese competition, and Michael could only find relief in deep and earnest profanity.

With the pagan influx began the mysterious disappearance of small valuables from the premises of Michael Doyle, licensed victualler. Sedate, fluffy old hens, hitherto noted for their strict propriety and regular hours, would leave the place at dead of night, and return from their nocturnal rambles never more; stay-at-home sucking-pigs, which had erstwhile absolutely refused to be driven from the door, corrupted by the new evil, absented themselves suddenly from the precincts of the Shamrock, taking with them cooking utensils and various other articles of small value, and ever afterwards their fate became a matter for speculation. At last a favourite young porker went, whereupon its lord and master, resolved to prosecute inquiries, bounced into the Mongolian camp, and, without any unnecessary preamble, opened the debate.

“Look here, now,” he observed, shaking his fist at the group, and bristling fiercely, “which av ye dhirty haythen furriners cum up to me house lasht noight and shtole me pig Nancy? Which av ye is it, so’t I kin bate him! ye thavin’ hathins?”

The placid Orientals surveyed Mr. Doyle coolly, and innocently smiling, said, “No savee;” then bandied jests at his expense in their native tongue, and laughed the little man to scorn. Incensed by the evident ridicule of the “haythen furriners,” and goaded on by the smothered squeal of a hidden pig, Michael “went for” the nearest Asiatic, and proceeded to “put a head on him as big as a tank,” amid a storm of kicks and digs from the other Chows. Presently the battle began to go against the Irish cause; but Mrs. Mickey, making a timely appearance, warded off the surplus Chinamen by chipping at their skulls with an axe-handle. The riot was soon quelled, and the two Doyles departed triumphantly, bearing away a corpulent young pig, and leaving several broken, discouraged Chinamen to be doctored at the common expense.

After this gladsome little episode the Chinamen held off for a few weeks. Then they suddenly changed their tactics, and proceeded to cultivate the friendship of Michael Doyle and his able-bodied wife. They liberally patronized the Shamrock, and beguiled the licensee with soft but cheerful conversation; they flattered Mrs. Doyle in seductive pigeon-English, and endeavoured to ensare the children’s young affections with preserved ginger. Michael regarded these advances with misgiving; he suspected the Mongolians’ intentions were not honourable, but he was not a man to spoil trade—to drop the substance for the shadow.

This state of affairs had continued for some time before the landlord of the Shamrock noticed that his new customers made a point of carrying off a brick every time they visited his caravansary. When leaving, the bland heathen would cast his discriminating eye around the place, seize upon one of the sun-dried bricks with which the ground was littered, and steal away with a nonchalant air—as though it had just occurred to him that the brick would be a handy thing to keep by him. The matter puzzled Mr. Doyle sorely; he ruminated over it, but he could only arrive at the conclusion that it was not advisable to lose custom for the sake of a few bricks; so the Chinese continued to walk off with his building material. When asked what they intended to do with the bricks, they assumed an expression of the most deplorably hopeless idiocy, and suddenly lost their acquaintance with the “Inglisiman” tongue. If bricks were mentioned they became as devoid of sense as wombats, although they seemed extremely intelligent on most other points. Mickey noticed that there was no building in progress at their camp, also that there were no bricks to be seen about the domiciles of the pagans, and he tried to figure out the mystery on a slate, but, on account of his lamentable ignorance of mathematics, failed to reach the unknown quantity and elucidate the enigma. He watched the invaders march off with all the loose bricks that were scattered around, and never once complained; but when they began to abstract one end of his licensed premises, he felt himself called upon, as a husband and father, to arise and enter a protest, which he did, pointing out to the Yellow Agony, in graphic and forcible language, the gross wickedness of robbing a struggling man of his house and home, and promising faithfully to “bate” the next lop-eared Child of the Sun whom he “cot shiftin’ a’er a brick.”

“Ye dogs! Wud yez shtale me hotel, so’t whin me family go insoide they’ll be out in the rain?” he queried, looking hurt and indignant.

The Chinaman said, “No savee.” Yet, after this warning, doubtless out of consideration for the feelings of Mr. Doyle, they went to great pains and displayed much ingenuity in abstracting bricks without his cognizance. But Mickey was active; he watched them closely, and whenever he caught a Chow in the act, a brief and one-sided conflict raged, and a dismantled Chinaman crawled home with much difficulty.

This violent conduct on the part of the landlord served in time to entirely alienate the Mongolian custom from the Shamrock, and once more Mickey and the Chows spake not when they met. Once more, too, promising young pullets, and other portable valuables, began to go astray, and still the hole in the wall grew till the after-part of the Shamrock looked as if it had suffered recent bombardment. The Chinamen came while Michael slept, and filched his hotel inch by inch. They lost their natural rest, and ran the gauntlet of Mr. Doyle’s stick and his curse— for the sake of a few bricks. At all hours of the night they crept through the gloom, and warily stole a bat or two, getting away unnoticed perhaps, or, mayhap, only disturbing the slumbers of Mrs. Doyle, who was a very light sleeper for a woman of her size. In the latter case the lady would awaken her lord by holding his nose—a very effective plan of her own— and, filled to overflowing with the rage which comes of a midnight awakening, Mickey would turn out of doors in his shirt to cope with the marauders, and course them over the paddocks. If he caught a heathen he laid himself out for five minutes’ energetic entertainment, which fully repaid him for lost rest and missing hens, and left a Chinaman too heart-sick and sore to steal anything for at least a week. But the Chinaman’s friends would come as usual, and the pillage went on.

Michael Doyle puzzled himself to prostration over this insatiable and unreasonable hunger for bricks; such an infatuation on the part of men for cold and unresponsive clay had never before come within the pale of his experience. Times out of mind he threatened to “have the law on the yalla blaggards;” but the law was a long way off, and the Celestial housebreakers continued to elope with scraps of the Shamrock, taking the proprietor’s assaults humbly and as a matter of course.

“Why do ye be shtealing me house?” fiercely queried Mr. Doyle of a submissive Chow, whom he had taken one night in the act of ambling off with a brick in either hand.

“Me no steal ’em, no feah—odder feller, him steal em,” replied the quaking pagan.

Mickey was dumb-stricken for the moment by this awful prevarication; but that did not impair the velocity of his kick—this to his great subsequent regret, for the Chinaman had stowed a third brick away in his pants for convenience of transit, and the landlord struck that brick; then he sat down and repeated aloud all the profanity he knew.

The Chinaman escaped, and had presence of mind enough to retain his burden of clay.

Month after month the work of devastation went on. Mr. Doyle fixed ingenious mechanical contrivances about his house, and turned out at early dawn to see how many Chinamen he had “nailed”—only to find his spring-traps stolen and his hotel yawning more desperately than ever. Then Michael could but lift up his voice and swear—nothing else afforded him any relief.

At last he hit upon a brilliant idea. He commissioned a “cocky” who was journeying into Ballarat to buy him a dog—the largest, fiercest, ugliest, hungriest animal the town afforded; and next day a powerful, ill-tempered canine, almost as big as a pony, and quite as ugly as any nightmare, was duly installed as guardian and night-watch at the Shamrock. Right well the good dog performed his duty. On the following morning he had trophies to show in the shape of a boot, a scrap of blue dungaree trousers,

half a pig-tail, a yellow ear, and a large part of a partially-shaved scalp; and just then the nocturnal visits ceased. The Chows spent a week skirmishing round, endeavouring to call the dog off, but he was neither to be begged, borrowed, nor stolen; he was too old-fashioned to eat poisoned meat, and he prevented the smallest approach to familiarity on the part of a Chinaman by snapping off the most serviceable portions of his vestments, and always fetching a scrap of heathen along with them.

half a pig-tail, a yellow ear, and a large part of a partially-shaved scalp; and just then the nocturnal visits ceased. The Chows spent a week skirmishing round, endeavouring to call the dog off, but he was neither to be begged, borrowed, nor stolen; he was too old-fashioned to eat poisoned meat, and he prevented the smallest approach to familiarity on the part of a Chinaman by snapping off the most serviceable portions of his vestments, and always fetching a scrap of heathen along with them.

This, in time, sorely discouraged the patient Children of the Sun, who drew off to hold congress and give the matter weighty consideration. After deliberating for some days, the yellow settlement appointed a deputation to wait upon Mr. Doyle. Mickey saw them coming, and armed himself with a log and unchained his dog. Mrs. Doyle ranged up alongside, brandishing her axe-handle, but by humble gestures and a deferential bearing the Celestial deputation signified a truce. So Michael held his dog down, and rested on his arms to await developments. The Chinamen advanced, smiling blandly; they gave Mr. and Mrs. Doyle fraternal greeting, and squirmed with that wheedling obsequiousness peculiar to “John” when he has something to gain by it. A pock-marked leper placed himself in the van as spokesman.

“Nicee day, Missa Doyle,” said the moon-faced gentleman, sweetly. Then, with a sudden expression of great interest, and nodding towards Mrs, Doyle, “How you sissetah?”

“Foind out! Fwhat yer wantin’?” replied the host of the Shamrock, gruffly; “t’ shtale more bricks, ye crawlin’ blaggards?”

“No, no. Me not steal ’em blick—odder feller; he hide ’em; build big house byem-bye.”

“Ye loi, ye screw—faced nayger! I seed ye do it, and if yez don’t cut and run I’ll lave the dog loose to feed on yer dhirty carcasses.”

The dog tried to reach for his favourite hold, Mickey brandished his log, and Mrs. Doyle took a fresh grip of her weapon. This demonstration gave the Chows a cold shiver, and brought them promptly down to business.

“We buy ’em hotel; what for you sell ’em—eh?”

“Fwhat! yez buy me hotel? D’ye mane it? Purchis th’ primisis and yez can shtale ivery brick at yer laysure. But ye’re joakin’. Whoop! Look ye here! I’ll have th’ lot av yez aten up in two minits if yez play yer Choinase thricks on Michael Doyle.

The Chinamen eagerly protested that they were in earnest, and Mickey gave them a judicial hearing. For two years he had been in want of a customer for the Shamrock, and he now hailed the offer of his visitors with secret delight. After haggling for an hour, during which time the ignorant Hi Yup of the contorted countenance displayed his usual business tact, a bargain was struck. The yellow men agreed to give fifty pounds cash for the Shamrock and all buildings appertaining thereto, and the following Monday was the day fixed for Michael to journey into Ballarat with a couple of representative heathens to sign the transfer papers and receive the cash.

The deputation departed smiling, and when it gave the news of its triumph to the other denizens of the camp there was a perfect babel of congratulations in the quaint dialogue of the Mongol. The Chinamen proceeded to make a night of it in their own outlandish way, indulging freely in the seductive opium, and holding high carouse over an extemporized fantan table, proceedings which made it evident that they thought they were getting to windward of Michael Doyle, licensed victualler.

Michael, too, was rejoicing with exceeding great joy, and felicitating himself on being the shrewdest little man who ever left the “ould sod.” He had not hoped to get more than a twenty-pound note for the dilapidated old humpy, erected on Crown land, and unlikely to stand the wear and tear of another year. As for the business, it had fallen to zero, and would not have kept a Chinaman in soap. So Mr. Doyle plumed himself on his bargain, and expanded till he nearly filled his capacious garments. Still, he was harassed to know what could possibly have attached the Chinese so strongly to the Shamrock.

They had taken samples from every part of the establishment, and fully satisfied themselves as to the quality of the bricks, and now they wanted to buy. It was most peculiar. Michael “had never seen anything so quare before, savin’ wanst whin his grandfather was a boy.”

After the agreement arrived at between the publican and the Chinese, one or two of the latter hung about the hotel nearly all their time, in sentinel fashion. The dog was kept on the chain, and lay in the sun in a state of moody melancholy, narrowly scrutinizing the Mongolians. He was a strongly anti-Chinese dog, and had been educated to regard the almond-eyed invader with mistrust and hate; it was repugnant to his principles to lie low when the heathen was around, and he evinced his resentment by growling ceaselessly. Sunday dawned. It was a magnificent morning; but the rattle of the Chinamen’s cradles and toms sounded from the creek as usual. Three or four suave and civil Asiatics, however, still lingered around the Shamrock, and kept an eye on it in the interests of all, for the purchase of the hotel was to be a joint-stock affair. These “Johns” seemed to imagine they had already taken lawful possession; they sat in the bar most of the time, drinking little, but always affable and genial. Michael suffered them to stay, for he feared that any fractiousness on his part might upset the agreement, and that was a consummation to be avoided above all things. They had told him, with many tender smiles and much gesticulation, that they intended to live in the house when it became theirs; but Mr. Doyle was not interested—his fifty pounds was all he thought of.

Michael was in high spirits that morning; he beamed complacently on all and sundry, appointed the day as a time of family rejoicing, and in the excess of his emotion actually slew for dinner a prime young sucking pig, an extravagant luxury indulged in by the Doyles only on state occasions. On this particular Sunday the younger members of the Doyle household gathered round the festive board and waited impatiently for the lifting of the lid of the camp-oven. There were nine children in all, ranging in years from fourteen downwards— “foine, shtrappin’ childer, wid th’ clear brain,” said the prejudiced Michael. The round, juicy sticker was at last placed upon the table. Mrs. Doyle stood prepared to administer her department—serving the vegetables to her hungry brood—and, armed with a formidable knife and fork, Michael, enveloped in savoury steam, hovered over the pig.

But there was one function yet to be performed—a function which came as regularly as Sunday’s dinner itself. Never, for years, had the housefather failed to touch up a certain prodigious knife on one particular hard yellow brick in the wall by the door, preparatory to carving the Sunday’s meat. Mickey examined the edge of his weapon critically, and found it unsatisfactory. The knife was nearly ground through to the backbone; another “touch-up” and it must surely collapse, but, in view of his changed circumstances, Mr. Doyle felt that he might take the risk. The brick, too, was worn an inch deep. A few sharp strokes from Mickey’s vigorous right arm were all that was required; but, alas! the knife snapped whereupon Mr. Doyle swore at the brick, as if holding it immediately responsible for the mishap, and stabbed at it fiercely with the broken carver.

“Howly Moses! Fwhats that?”

The brick fell to pieces, and there, embedded in the wall, gleaming in the sunbeam, was a nugget of yellow gold. With feverish haste Mickey tore the brick from its bedding, and smashed the gold-bearing fragment on the hearth. The nugget was a little beauty, smooth, round, and four ounces to a grain.

The sucking pig froze and stiffened in its fat, the “taters” and the cabbage stood neglected on the dishes. The truth had dawned upon Michael, and, whilst the sound of a spirited debate in musical Chinese echoed from the bar, his family were gathered around him, open-mouthed, and Mickey was industriously, but quietly, pounding the sun-dried brick in a digger’s mortar. Two bricks, one from either end of the Shamrock, were pulverized, and Michael panned off the dirt in a tub of water which stood in the kitchen. Result: seven grains of waterworn gold. Until now Michael had worked dumbly, in a fit of nervous excitement; now he started up, bristling like a hedgehog.

“Let loose th’ dog, Mary Melinda Doyle!” he howled, and, uttering a mighty whoop, he bounded into the bar to dust those Chinamen off his premises. “Gerrout!” he screamed—“Gerrout av me primises, ye thavin’ crawlers!” And he frolicked with the astounded Mongolians like a tornado in full blast, thumping at a shaven occiput whenever one showed out of the struggling crowd. The Chinamen left; they found the dog waiting for them outside, and he encouraged them to greater haste. Like startled fawns the heathens fled, and Mr. Doyle followed them, howling:

“Buy the Shamrock, wud yez! Robbers! Thaves! Fitch back th’ soide o’ me house, or Oi’ll have th’ law onto yez all.”

The damaged escapees communicated the intelligence of their overthrow to their brethren on the creek, and the news carried consternation, and deep, dark woe to the pagans, who clustered together and ruefully discussed the situation.

Mr. Doyle was wildly jubilant. His joy was only tinctured with a spice of bitterness, the result of knowing that the “haythens” had got away with a few hundreds of his precious bricks. He tried to figure out the amount of gold his hotel must contain, but again his ignorance of arithmetic tripped him up, and already in imagination Michael Doyle, licensed victualler, was a millionaire and a J.P.

|

| Quite another Shamrock Hotel, this one at Sandhurst, now Bendigo. |

The Shamrock was really a treasure-house. The dirt of which the bricks were composed had been taken from the banks of the Yellow Creek, years before the outbreak of the rush, by an eccentric German who had settled on that sylvan spot. The German died, and his grotesque structure passed into other hands. Time went on, and then came the rush. The banks of the creek were found to be charged with gold for miles, but never for a moment did it occur to anybody that the clumsy old building by the track, now converted into a hotel, was composed of the same rich dirt; never till years after, when by accident one of the Mongolian fossickers discovered grains of gold in a few bats he had taken to use as hobs. The intelligence was conveyed to his fellows; they got more bricks and more gold—hence the robbery of Mr. Doyle’s building material and the anxiety of the Mongolians to buy the Shamrock. Before nightfall Michael summoned half-a-dozen men from “beyant,” to help him in protecting his hotel from a possible Chinese invasion. Other bricks were crushed and yielded splendid prospects. The Shamrock’s small stock of liquor was drunk, and everybody became hilarious. On the Sunday night, under cover of the darkness, the Chows made a sudden sally on the Shamrock, hoping to get away with plunder. They were violently received, however; they got no bricks, and returned to their camp broken and disconsolate.

Next day the work of demolition was begun. Drays were backed up against the Shamrock, and load by load the precious bricks were carted away to a neighbouring battery. The Chinamen slouched about, watching greedily, but their now half-hearted attempts at interference met with painful reprisal. Mr. Doyle sent his family and furniture to Ballarat, and in a week there was not a vestige left to mark the spot where once the Shamrock flourished. Every scrap of its walls went through the mill, and the sum of one thousand nine hundred and eighty-three pounds sterling was cleared out of the ruins of the hostelry. Mr. Doyle is now a man of some standing in Victoria, and as a highly respected J.P. has often been pleased to inform a Chinaman that it was “foive pound or a month.”

Comments

Post a Comment